Alexandrium catenella

- Produces saxitoxin, causing Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning (PSP)

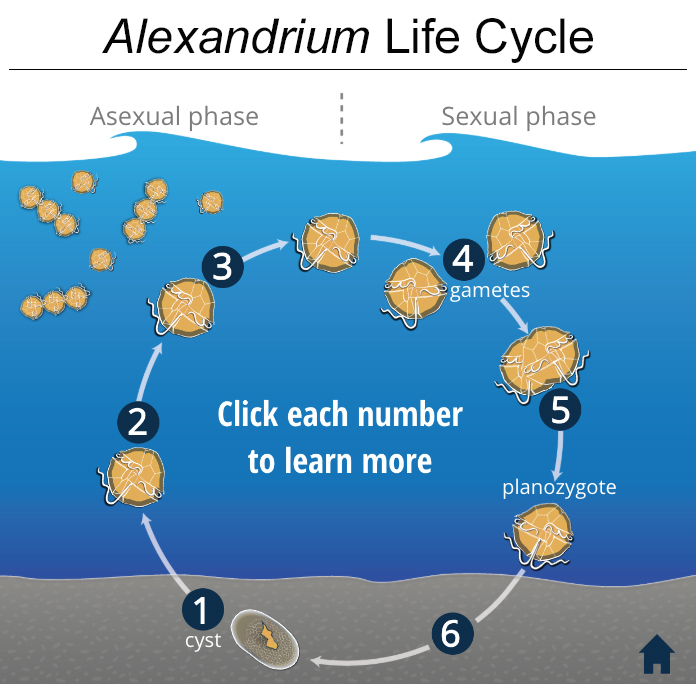

- Alexandrium spend winter in the sediment as a resting cyst stage, blooms begin in spring

- PSP occurs when people consume contaminated shellfish, the syndrome is characterized by neurological symptoms

- PSP is well-monitored in New England - when toxins are detected above safety thresholds, shellfish beds closures are enacted

What is Alexandrium catenella?

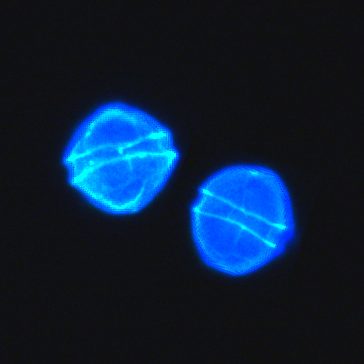

The most well-known and costly harmful algal bloom syndrome in New England is Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning (PSP), caused by blooms of the toxin-producing dinoflagellate Alexandrium catenella. PSP is a life threatening syndrome associated with the consumption of seafood products (often shellfish) contaminated with the neurotoxins known collectively as saxitoxins (STXs). Symptoms are purely neurological and their onset is rapid, appearing as early as ten minutes to three hours following consumption of contaminated food. Duration of effects is generally a few days in non-lethal cases. PSP is prevented by large-scale proactive monitoring programs (assessing toxin levels in mussels, oysters, scallops, clams) and rapid closures of suspect or demonstrated toxic areas to harvest. There is no risk to people who consume the flesh of fish, lobsters, and shrimp or to people who swim in the ocean. There are now over 30 recognized morphological species of Alexandrium, and around half of these species are known to produce toxins.

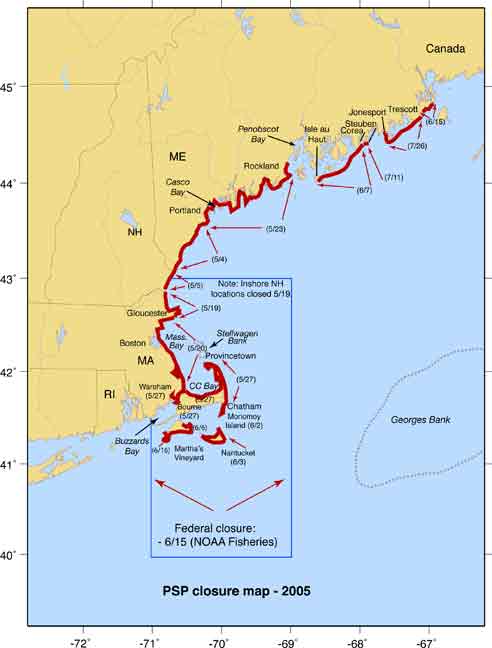

In New England, PSP has been recurrent and widespread in the region going back decades. Bloom concentrations vary from year to year, but 1972 and 2005 were particularly devastating years in terms of the extent and intensity of A. catenella blooms and PSP outbreaks. The establishment of recurring A. catenella blooms and PSP in temperate regions such as New England is enabled by the life cycle of A. catenella, which involves alternation between asexual and sexual reproduction (see Alexandrium Life Cycle graphic). The motile cells of A. catenella originate from the germination of dormant cysts that accumulate in bottom sediments and allow the species to survive cold winter temperatures and unfavorable growing conditions. The cysts can also be resuspended by tides and storms.

New England states have well established monitoring programs for PSP toxicity and enact shellfishing bed closures on a near annual basis to safeguard public health.

What is the history of Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning in New England?

Prior to 1972, PSP toxicity was historically restricted to the far eastern sections of Maine near the Canadian border, with the first documented PSP in Maine in 1958. In 1972, a massive, visible bloom of A. catenella stretched from southern Maine through New Hampshire and into Massachusetts, causing toxicity in these states for the first time. Virtually every year since the 1972 outbreak, western Maine has experienced PSP outbreaks, and on a less-frequent basis, New Hampshire and Massachusetts have as well. This pattern has been viewed as a direct result of Alexandrium cysts being retained in western Gulf of Maine waters once introduced there by the 1972 bloom. Natural current and wind patterns usually keep the cells from flowing into nearshore waters of southern New England in most years.

Significant regional-scale A. catenella blooms occurred in both 2005 and 2006. The 2005 event was longer, extended further to the south and had higher cell concentrations and shellfish toxicities. In 2007, toxicity was restricted to sections of Eastern and Western Maine. A large, offshore bloom was documented on Georges Bank as well. In 2008, a significant regional-scale A. catenella bloom occurred. Toxicity was particularly high in eastern Maine but also extended south to Massachusetts Bay and parts of Cape Cod. An offshore bloom of the species was also detected on Georges Bank. It is noteworthy that this bloom was predicted several months in advance based on the abundance of A. catenella cysts in Gulf of Maine sediments (see press release). The 2009 bloom began with the typical pattern of toxicity in and near Casco Bay, expanding to western Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts with a subsequent decrease in early June. However, mid to late June showed a dramatic increase in cell abundance in the Bay of Fundy, and shortly thereafter in eastern Maine. Toxicity then spread rapidly along the entire Maine coast, which had very high levels of toxicity through much of the summer. A visible bloom of A. catenella was observed in early July near Portsmouth, NH. The 2010 bloom season was marked by low toxicity and low numbers of cells throughout the region. 2011 proved to be a moderate year, with closures in western Maine to the south shore of Boston, while eastern Maine saw closures in the easternmost regions, bordering Canada. 2012 was also a moderate year with toxicity throughout most of eastern Maine and western Maine down to the New Hampshire / Massachusetts border. Parts of Massachusetts Bay were also closed. 2013 and 2014 were marked by low toxicity throughout the region.

Resources and References

Fact Sheets

Monitoring

Research Papers

- Anderson et al. 2005. Initial observations of the 2005 Alexandrium fundyense bloom in southern New England: General patterns and mechanisms. Deep-Sea Research II 52(2856-2876)

- Anderson, D.M. 1997. Bloom dynamics of toxic Alexandrium species in the northeastern U.S. Limnology and Oceaongraphy 42(1009-1022)